What’s Mom Got to Do With It? Maternal Impression in Western Medicine

Imagine this: you are pregnant and are overcome with a yearning for seafood, mussels in particular. Do you think this desire could be so strong that it could influence the development of your fetus?

To the contemporary reader, that idea seems ridiculous. Yet, this is exactly a story told in Thomas Fienus’ 1608 book A Treatise on the Power of the Imagination. According to the tale, a pregnant mother’s desire for mussels was so strong that her child was born with a head shaped like a mussel. Fienus then describes the child living for eleven years, fed through its “gaping bivalve,” before finally perishing due to a cracked shell.

Fienus, a prominent Swiss physician at the time, does admit a little skepticism at this account. Yet he spends over 150 pages of his treatise describing with full credulity other such stories of mothers scared by wolves whose children were born with wolf-like features, and of mothers who craved cherries and strawberries and whose children were born with birthmarks resembling these fruits.

These are examples of “maternal impression.” Maternal impression was a theory that an emotional or physical stimulus experienced by a pregnant woman* could influence the development of her fetus. It was used to explain birth defects and other congenital disorders for centuries. Often the impression was a direct analog in which a desire, trauma or even the sight of something could manifest itself on the fetus.

Throughout this path, we will look at some of the ideas behind the concept of maternal impression as they have appeared throughout Western medicine.

*While the Historical Medical Library acknowledges that people who do not identify as a woman can become pregnant and give birth, we will use the term woman and women in our writing on this subject to reflect contemporary usage as it relates to the primary sources consulted.

Figure prodigieuse d'un enfant ayant la face d'une Grenoüille, 1614

Les oeuvres d’Ambroise Paré., page 1022.

Paré’s 13 Reasons for Teratogenesis

The influence of Ambroise Paré (1510?-1590) on medical history is vast and varied. A French barber-surgeon who served kings, Paré is considered to be one of the fathers of surgery. He pioneered many of his techniques on the battlefields of 16th century Europe. A subject of particular fascination for Paré was the monstrous. Many of the woodcuts in his magnum opus Des Oeuvres (1585) depict these wonders. His 1573 book, Des Monstres, devoted itself to the subject and included the following thirteen reasons why monstrous births occurred:

The first is the glory of God.

The second, His wrath.

The third, too great a quantity of semen.

The fourth, too small a quantity.

The fifth, imagination.

The sixth, the narrowness or smallness of the womb.

The seventh, the unbecoming sitting position of the mother, who, while pregnant, remains seated too long with her thighs crossed or pressed against her stomach.

The eighth, by a fall or blows struck against the stomach of the mother during pregnancy.

The ninth, by hereditary or accidental illnesses.

The tenth, by the rotting or corruption of the semen.

The eleventh, by the mingling or mixture of seed.

The twelfth, by the artifice of wandering beggars.

The thirteenth, by Demons or Devils.

The ones bolded above are particularly relevant to a discussion of maternal impression. Paré cites children born covered in dark hair (possibly hypertrichosis) as caused by the sight of something wild. He warns “truly I think it best to keep the woman all the time she goeth with child, from the sight and of such shapes and figures.”

Another story of maternal impression from Paré is that of a child born with the face of a frog in 1517. As Paré recounts, the child’s mother had come down with a serious illness resulting in fever. On the advice of a neighbor, she attempted a cure in which she should take a live frog and hold it in her hands until it died. That night, she went to bed still holding the frog and “her and her husband embraced and conceived; thus [a monster] was born by virtue of her imagination.”

Paré's belief in maternal impression as a cause of monstrosity is of note due to the influence his writing on medicine had throughout the rest of the early modern period.

Manifestations of Maternal Impression

This section explores more about how physicians between 1500 - 1900 defined “maternal impression” and how they thought those impressions impacted fetal development.

Mother’s Marks

In the vast compendium that is Girolamo Cardano’s (1501-1576) Opera Omnia (1663), he discusses a great number of subjects. Cardano, an epitome of the Italian “renaissance man,” asserts that if a pregnant woman has a desire for some food or other want, then when the child is born, they will have a mark on their skin in the form of that desire. These are what were known as “mother’s marks.”

The ideas surrounding mother’s marks evolved over time. At first, the explanation for mother’s marks corresponded to an explanation for how people and animals came to be of a coloration different from that of its/their parents. Before the early modern era, most instances of maternal impression were limited to this sort of impression, one of marking or coloration. In the 16th Century this idea is expanded to include hypertrichosis, excessive hair growth, as well as other “monstrosities.”

Monstrosities of a Mother’s Making

The idea that the power of thought could affect an unborn fetus was commonly held among medical practitioners before and up through the beginning of the early modern period. Yet it was only in the 17th Century when this concept of maternal impression took root as a cause of monstrosities.

Jean Riolan (1580-1657), in his 1649 book, Opuscula anatomica nova, described one such case. A “double-fetus,” more commonly known as a conjoined twin, was born to a mother in 1605. The cause, according to Riolan, was the mother having looked at pictures of demons. Many believed at the time that the devil could directly affect an unborn fetus. In this case, however, the cause was the mother having seen, and then meditated upon, the images of demons that was the cause.

Riolan, was somewhat cautious in his belief in maternal impression. He believed that though the imagination could alter the properties of the fetus, it could not change the species. Fortunio Liceti (1577-1657), a prominent Italian physician, philosopher, and scientist, went further. He did not believe “mutilated monstrosities and those showing excessive parts” resulted from maternal impression; instead Liceti referred to monstrosities as lusus naturae (nature’s game).

As in Paré’s thirteen reasons, it was not always the imagination that caused a maternal impression, but rather an external event. Nicolas Culpeper (1616-1654), was an English botanist, herbalist, physician and astrologer. In his book A directory for midwives (1671) he described various accounts of maternal impression in the chapter “On Monsters.” Culpeper claimed that one woman, Anne Troperim, gave birth to two serpents after drinking from a brook near Basil, having swallowed the spawn of a serpent.

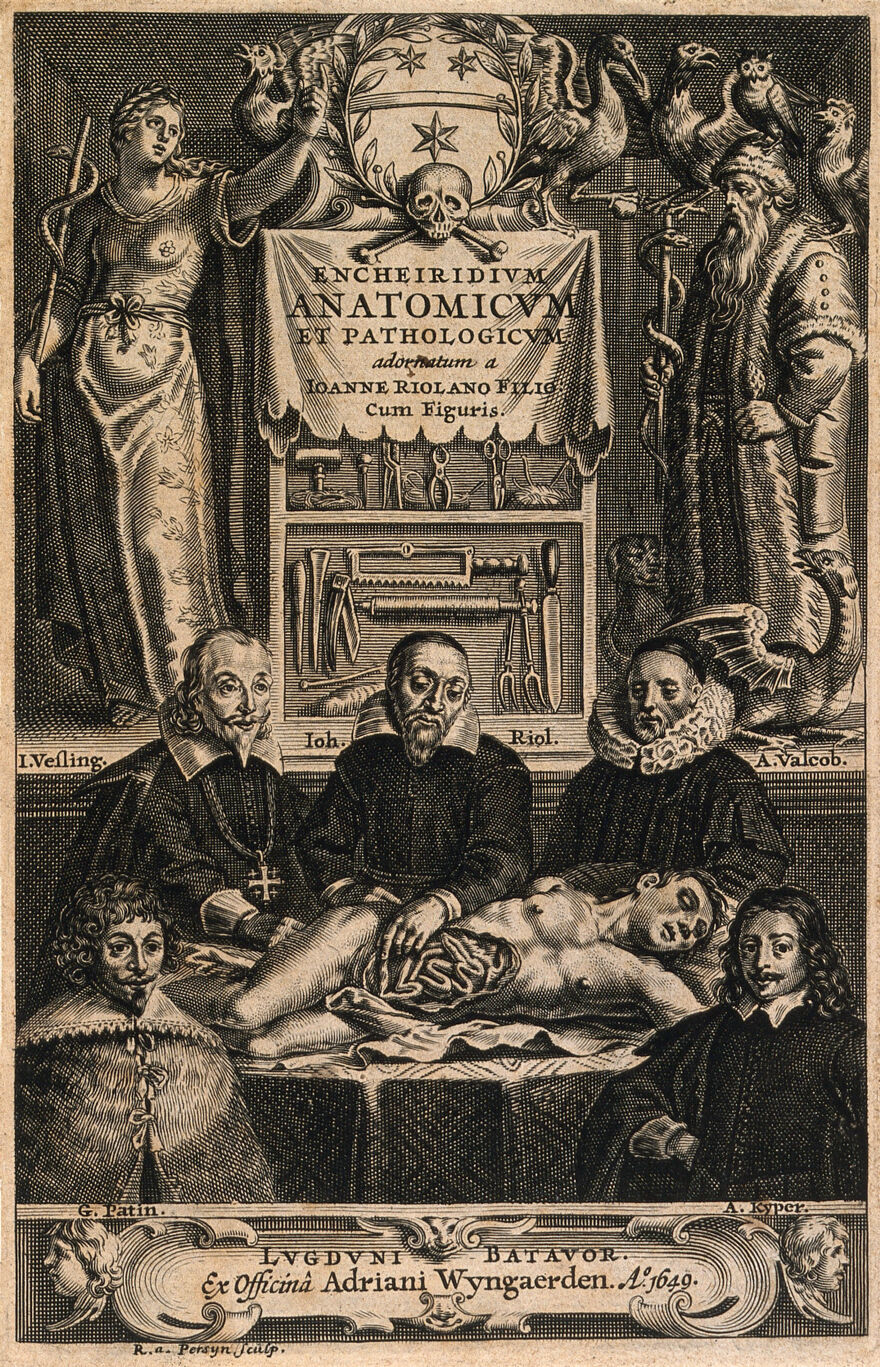

An anatomical dissection by Jean Riolan the younger (1580-1657). Engraving of 1649 by Renier van Persyn after a design of 1626 by Crispijn de Passe the second. Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection.

External Impressions

As shown in Culpeper’s story of Anne Troperim, maternal impression is not always located in the mind of the mother. Many cases involve an external event or trauma as the catalyst.

One such story is from Nicolas Malebranche (1638-1715), a French priest and philosopher. His most famous work, De la recherche de la vérité or Treatise Concerning the Search for Truth, was published in 1674.

Malebranche’s story is of a woman who, after witnessing a criminal broken at the wheel , a common form of public execution at the time, gave birth to a developmentally disabled child. This child’s limbs were fractured in the same locations as had the criminal’s been broken. One possible medical explanation for this is the congenital disease osteogenesis imperfecta, also known as brittle bone disease, which results from one’s inability to produce type 1 collagen, a protein used in bone creation.

The execution of conspirators by means of breaking them on the wheel and crucification in Lisbon in 1759. Etching with engraving. Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Modern Science and the Limits of Maternal Impression

Many of the ideas and scenarios presented here as examples of maternal impression seem fantastic or even absurd to the modern reader. Indeed, the continuing scientific revolutions of the 20th century, such as those in the field of genetics, did much to dispel the hold of maternal impression on western medicine. However, articles dating to the 1990’s continue to state that, in some cases, maternal impression is a real and literal exchange between a mother and the fetus she carries.

Echoes of maternal blame still can be heard in issues that have surrounded fetal development over the last 40 years. For example, the threat of “crack babies” in the 1980s and 1990s, and the possible long term impacts of prenatal cocaine exposure, caused widespread panic at the possible cost to society of caring for disabled children. However, the recent reaction to outbreaks of the Zika virus and the microcephaly that could occur in children born to affected mothers points to the success of educating people about the connections between mother, child and the environment, further limiting the impact of maternal impressions.

Tableux 1 from Gottlieb Friderici's (1693 – 1742) Monstrorum humanum rarissimum, or The rarest of human monsters (1737), depicting the Hühnermensch, or “Chicken man."

Controversy and Debate

This sections focuses on some controversial claims of maternal impression, as well as debates that surrounded the controversies.

Mary Toft, the Woman Who Gave Birth to Rabbits

In September 1726, news spread around England about a young servant woman who had given birth to several rabbits. After having miscarried a month earlier, Mary Toft still appeared pregnant, and after a labor attended by her neighbor, Toft gave birth to what “looked like a liverless cat.” Toft’s family called the physician from a nearby town who, upon visiting Toft, was presented with many animal parts.

Over the course of the next month, the physician recorded that Toft had given birth to the legs of a cat, a rabbit’s head and nine dead baby rabbits. Having witnessed these miraculous births, the physician sent letters to many of England’s prominent physicians and scientists. News even reached the court of King George I, who sent two people to investigate the matter.

The investigators had some doubts about the veracity of these strange births, but decided to keep their thoughts private until the matter was settled. However, it was too late to stop the torrent of interest that was generating throughout England. Soon the story came to the attention of the national press, causing a sensation.

Toft explained that earlier that year she had been working in a field and was startled by a group of rabbits. Toft and another woman chased after the rabbits, but failed to catch them. "That same Night she dreamt she was in a Field with those two Rabbets in her Lap, and awakened with a sick Fit, which lasted till Morning; from that time, for above three months, she had a constant and strong desire to eat Rabbets, but being very poor and indigent cou'd not procure any."

Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism, print, William Hogarth (MET, 91.1.117). Source: Wikipedia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Turner/Blondel Debate and Beyond

The 18th Century began with an attempt to reconcile traditional beliefs with the new methods of scientific inquiry. James Augustus Blondel (ca. 1666-1734), wrote a much read response to the Toft case titled The strength of imagination in pregnant women examin'd (1729), which you can read in its entirety on our digital library. Blondel observed that impressions often occurred for which no mark or anomaly followed, and that many abnormal births occurred for which no impression could be alleged.

Blondel’s response to the Toft case sparked a public debate between him and a Dr. Daniel Turner (1667-1741). Turner was a British physician who wrote on diseases of the skin as well as a number of surgical manuals. In response to Blondel, Turner wrote a pamphlet that recounted many supposed cases of maternal impression, including those told by Fienus and Malebranche. Blondel was the victor in this exchange, resulting in a perceptible change in attitude throughout England. Bondel's work was translated into French, Italian, German and Dutch. This resulted in other pamphlets appearing throughout Europe that also refuted maternal impression.

William Smellie (1697-1763), was a famed Scottish man-midwife whose work A treatise on the theory and practice of midwifery is a foundational text in obstetrics. In the work, Smellie echoed one of Blondel’s main arguments against maternal impression. Smellie states, “I have delivered many women of children who retained no marks, although the mothers had been frightened and surprised by disagreeable objects and were extremely apprehensive about such consequences.” Smellie’s vast influence on the burgeoning field of obstetrics, and the reach of his treatise, helped to solidify Blondel’s ideas.

This shift in perspective in the 18th century is exemplified by the case of the Hühnermensch, or “Chicken man." In 1735, in a small town near Leipzig, Germany, 28-year-old Johanna Sophia Schmeid delivered a stillborn baby, her fourth child. This baby was born with numerous physical anomalies, including a comb-like structure on the head; large, round eyes; and hands with lengthy fingers and “claws exactly like those of a chicken.” A local physician, Gottlieb Friderici (1693 – 1742), performed an autopsy and published his findings in the essay, Monstrorum humanum rarissimum, or The rarest of human monsters (1737). The essay included detailed anatomical drawings and a proto-case study of the pregnancy.

Friderici noted the physical nature of Schmeid (short, slender, with a “choleric-melancholic” temperament) and the physical nature of her husband, whom Friderici noted as being a “hunchback.” Friderici also examined Schmeid’s three prior pregnancies, and compared them to the fourth. It was noted that this fourth pregnancy did not progress as did the prior three, with fetal movements ceasing midway through the pregnancy.

While Friderici concluded that the deformities were the result of crossbreeding between human and rooster, attributable to some form of maternal impression, it is important to note that his detailed autopsy, and his examination of the Schmeid’s minor dysmorphic features, provided the first detailed description of Roberts syndrome, a genetic condition that would not be conclusively defined until 1919.

The Skepticism of Science

Advances in 19th Century medical science offered further skepticism to the concept of maternal impression. August Förster (1822-1865), a German anatomist who wrote on maternal impression, rejected the many stories found in medical literature. Förster's many reasons for this rejection came from his scientific understanding. One argument was that most malformations occur during the first week or month of pregnancy. This is before the mother usually has any idea that they are carrying a fetus.

Others, such as the French physician Ernest Martin (1876-1934), sought a medical explanation for maternal impression. In his 1880 book, Histoire des monstres: depuis l'antiquité jusqu'à nos jours, Martin claims that the imagination plays a mechanical role in the creation of monsters. This mechanical role occurs when the mother’s mental state is conveyed through the nervous system. This caused the uterus to contract, bringing the fetus under pressure and causing malformations.

Through the efforts of those such as Turner and Martin, beliefs in maternal impression continued through the nineteenth century. A manuscript by Dr. William Turner held at the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia is an example. Dated 1876, it is an address to the Philadelphia County Medical Society, which can read in its entirety here. Turner, while more cautious than many of his earlier predecessors, asserted that maternal impression is a real phenomenon. Like Martin, he used medical explanations for the phenomenon.

Modern Science and the Limits of Maternal Impression

Many of the ideas and scenarios presented here as examples of maternal impression seem fantastic or even absurd to the modern reader. Indeed, the continuing scientific revolutions of the 20th century, such as those in the field of genetics, did much to dispel the hold of maternal impression on western medicine. However, articles dating to the 1990’s continue to state that, in some cases, maternal impression is a real and literal exchange between a mother and the fetus she carries.

Echoes of maternal blame still can be heard in issues that have surrounded fetal development over the last 40 years. For example, the threat of “crack babies” in the 1980s and 1990s, and the possible long term impacts of prenatal cocaine exposure, caused widespread panic at the possible cost to society of caring for disabled children. However, the recent reaction to outbreaks of the Zika virus and the microcephaly that could occur in children born to affected mothers points to the success of educating people about the connections between mother, child and the environment, further limiting the impact of maternal impressions.